DEAD MAN WALKING

One man went to a cruel and unusual death for us. How we respond to this is the measure of our life.

Some time ago I came across a Texan website (it had to be Texan) which features the menus of the final meals people eat before they are executed. One man chose ‘six pieces of French toast with syrup, jelly, butter, six barbecued spare ribs, six pieces of well-burnt bacon, four scrambled eggs, five well-cooked sausage patties, French fries, three slices of cheese, two pieces of yellow cake with chocolate fudge icing and four cartons of milk’. I suppose he made the ghoulish calculation that indigestion would not be a problem. The most common orders are apparently for burgers, chicken, fries and the odd pizza. You might think it’s rather morbid to take such an interest in the last meal of a man about to be executed – but isn’t this what we do with Holy Communion?

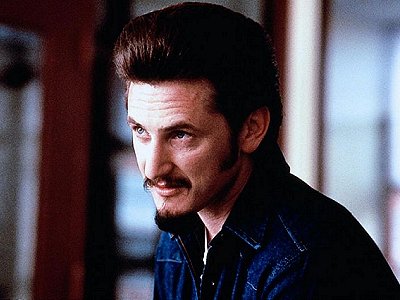

Some US states have the death penalty as a final sanction; Britain does not, indeed cannot if it wishes to remain a part of the European Union. If you want to see the issues surrounding this controversial topic set out in balanced yet unsparing details, you might want to watch the film ‘Dead Man Walking’ with Susan Sarandon and Sean Penn. On one hand it sets out the unremitting pain of the families of murder victims and how being bereaved this way practically ends life as you know it, so overwhelming is the horror. On the other hand it shows how gruesome state execution is. Even watching the pretend execution of another human being left me feeling unsettled and diminished.

In the US, the former attorney-general of Georgia, Michael Bowers, who is an advocate of the death penalty, has said in a refreshingly candid admission that any system of capital punishment will sometimes kill an innocent person. In one state some time ago, executions were suspended after a team of investigative journalists discovered that at least four people on death row were innocent but found guilty because their legal defences had been so shambolic. Poverty and race are recurrent factors in the profile of death-row inmates. It is hard to imagine what it must be like to go to your death an innocent person; to embrace the terrible humiliation and to know what impact it would have on those who love you.

The description of the crucifixion of Jesus in the Gospels is sparse and understated, in direct contrast to the emotive and exhibitionist culture we live in. In spite of their restraint, the writers of the New Testament manage to provoke a range of profound responses in people. Christ was sacrificed for our sin and this is a theological interpretation we should grasp in order to make an adequate spiritual response. Yet the human reality is that someone went voluntarily to an unjust public execution in order to save us.

There is something of a dichotomy in how Jesus approached his own execution. On one hand he showed great sorrow and distress, confronting and questioning God directly at both Gethsemane and Calvary. On the other hand he went silently, with no curses, recrimination or anger against the people who did this to him. We should all make our own personal response to this death.

It is the practice in the United States for a man being led from his cell to the death chamber to be accompanied by the jailor’s contrived and intimidating cry: ‘make way, there’s a dead man walking’. It’s a chilling phrase. Just occasionally there might be a last minute reprieve (something Jesus himself sought in the Garden) but it’s very rare. A dead man walking is both alive and dead. He is more certainly about to die than anyone else, as the whole force of the State is mustered to enable this. A dead man walking occupies a strange and terrible land between life and death.

Jesus himself had already self-consciously occupied this precarious place from that point in his ministry when he informed the disciples he must go up to Jerusalem and die. Unjust deaths are usually cruel and meaningless, but this particular death was transformed by the resurrection. If hours before his death Jesus had been a dead man walking, by Easter Day he was in a very different sense a dead man walking – up and about and door-stepping his bewildered friends.

The paradox of the Gospel is that Christ’s followers are dead men and dead women walking also. ‘I have been crucified with Christ’ says St. Paul, ‘and it is no longer I who live, but it is Christ who lives in me. And the life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me.’ Christians have died to their old way of life, and are presented with a lasting choice: are they going to live for God or live for themselves? The logic of this sacrifice by Jesus points only in one direction. As the Victorian cricketer and missionary C.T. Studd said: ‘if Jesus be the Son of God and died for me, then no sacrifice can be too big for me to make for him’. Studd saw the implications of the cross. Unless he buried his head in the sand and pretended he had not heard, the only response with any integrity was to give himself, body and soul, to Jesus.

In the middle of noisy and crowded lives, with endless tasks and countless choices, this core belief of ours should have the clarity to inspire us to renewed levels of trust. When we take bread and wine, the last meal of our condemned saviour and the regular meal of those who have passed from death to life with him, we should remind ourselves that this man went to a death involving cruel and unusual punishment to sacrifice his life for us personally, and ask ourselves how exactly we are going to respond to it.

POPULAR ARTICLES

Obama's Covert Wars

The use of drones is going to change warfare out of all recognition in the next decades.

Through A Glass Starkly

Images of traumatic incidents caught on mobile phone can be put to remarkable effect.

What Are British Values?

Is there a British identity and if so, what has shaped the values and institutions that form it?